This blog is part of the Large Language Model Agents course I took at UC Berkeley. As LLMs revolutionize our everyday life, this course sheds light on how LLM agents—LLM-powered systems that can reason and take actions to interact with their environment—will open new frontiers in task optimization and personalization. Inspired by this journey from LLM foundations over reasoning and planning to embodied agents, I would like to use this blog to summarize my learnings from the 12 lectures of this course. I will focus on the foundational paradigms in LLM agents and briefly explore AutoGen, Microsoft’s Python framework for orchestrating agents. A rudimentary knowledge of LLMs is expected.

What are agents?

While the literature does not provide a widely accepted definition for LLM agents, an agent can be described as an intelligent system that interacts with some environment. Think of the environment as every possible system you can imagine, e.g., the real world, a web application, a GitHub repo, or a game.

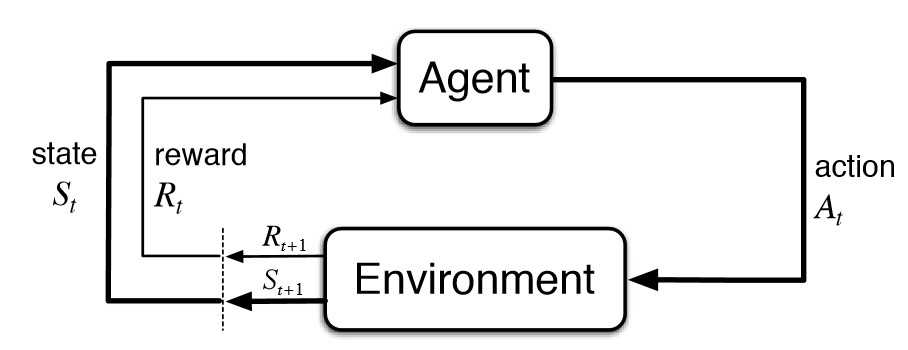

Traditionally, in the field of machine learning, the term “agent” is used in reinforcement learning, where an agent’s policy is trained to maximize a reward retrieved from its environment upon performing an action based on its current state.

Schematic overview of agents in RL [1]

Now that LLMs have reached or even surpassed human intelligence (OpenAI’s GPT-4 managed to score an IQ of 120 on the Norway Mensa IQ test, where humans average 103) and are trained on data with internet-level scale, yielding a system skilled in a wide array of disciplines, it seems reasonable that LLMs can directly be employed to build such “intelligent” systems without having to tune their weights according to the task and environment. This realization paved the way for LLM agents, which some believe will create the value GenAI has been praised to provide through task optimization and personalization. Already today, there are impressive demos of LLM agents popping up left and right (e.g., GitHub Copilot solving coding issues, Tesla’s Optimus serving beer, Anthropic’s Claude booking flights), yet reliable real-world applications are still missing.

Tesla's Optimus serving beer [2]

Agent features

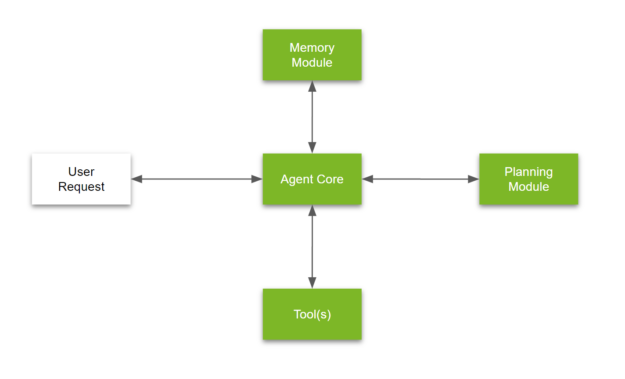

As discussed in the last paragraph, the LLM is what is supposed to bring the “intelligence” into the system. The sampling procedures employed in LLMs during inference make the model probabilistic, which brings advantages and disadvantages. On the upside, the models are much more versatile than typical digital systems with their tree-based logic. They are not limited to a specific set of input formats and requests. On the downside, this probabilistic nature, paired with the mix of training data and post-training procedures, also leads to hallucinations, which are not yet fully understood. Hence, to make LLM agents reliable and also use them in high-stakes applications, we need to do more engineering around the LLM. While best practices are still evolving in this relatively new field, there are already some features that you will find in almost every LLM agent (see the sketch of a typical LLM agent system design below).

Schematic overview of LLM agents system architecture [3]

Prompt Engineering

Prompt engineering might be the most important feature in agent systems. As we know, LLMs are queried via text messages called prompts. The two most important prompts used for almost every interaction with an LLM are the user prompts and the system prompt. Due to the autoregressive nature of LLMs, pre-pending a good prompt to the model generation will increase the conditional probability of a satisfying completion. Hence, over time, prompting has become an art, describing many best practices to optimize prompts for better results. This includes techniques like adding context, few-shot prompting, and chain-of-thought, which we will discuss shortly. Effective prompt engineering not only improves the reliability of LLM agents but also mitigates issues like hallucinations and irrelevant responses.

Here I would like to highlight Stanford’s DSPy framework, which is a more “scientific” approach to prompt engineering where a compiler optimizes prompts dynamically based on custom output metrics.

Memory

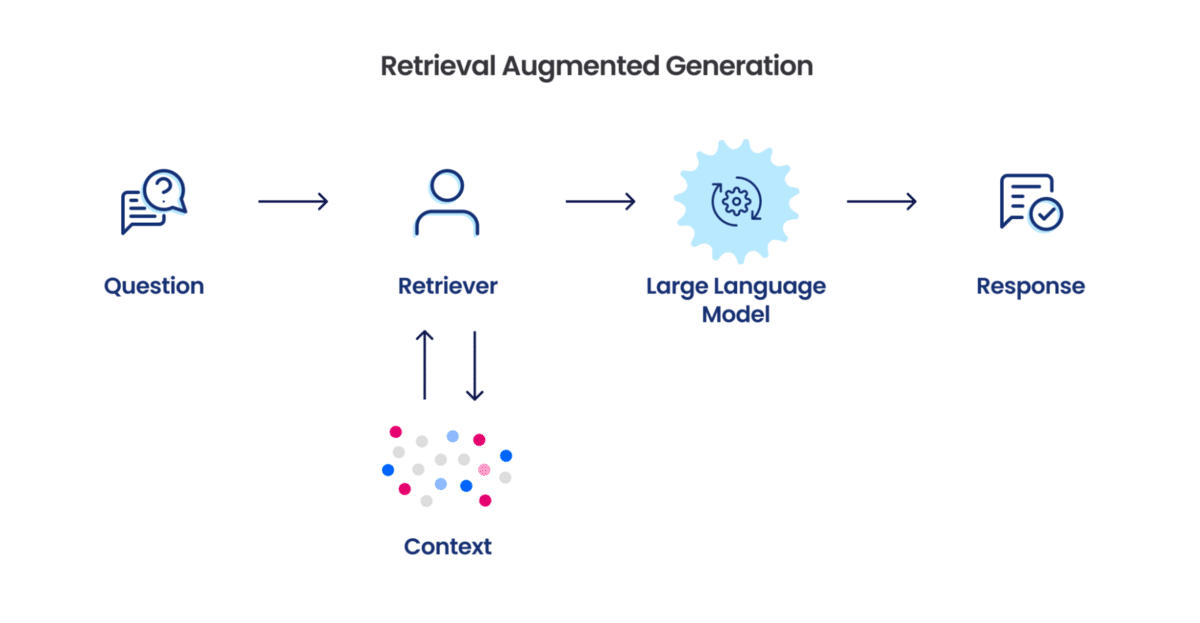

Memory seems like one of the most intuitive features. While internet-scale pre-trained LLMs already accumulate a lot of generic knowledge about the world, the LLM does not have all the details needed for most agent use cases. It does not know the customer ID of the client it might be talking to, the history of the chat it had with another person three days ago, or the cultural guidelines for client communication of the company it represents. While there are more sophisticated approaches, such as memory editing and injection in the LLM via fine-tuning, a simple technique called retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) has been widely used in agents.

In RAG, the knowledge to be injected into the LLM is chunked into smaller pieces, tokenized, embedded, indexed, and stored as vectors in a vector database. When the system is queried, the most relevant pieces of information in the vector database are identified via similarity search in the embedding space, transformed to natural language, and used to enrich the prompt fed into the model. Since a vector database functions similarly to other databases, developers can orchestrate the “memory” database as needed for the specific agent system (e.g., event-based data ingestion or retrieval of the entire database for every query).

Schematic overview of RAG [4]

Reasoning

Reasoning is the reason we humans can learn and generalize from only a few examples. Hence, wanting agents to reason might seem trivial, yet the research community is still trying to figure out how to orchestrate models to imitate human reasoning. Even in chatbot use cases, where LLMs are only queried once, reasoning is more complicated than initially thought.

Initial findings showed that LLM performance improved when using reasoning techniques like chain-of-thought (instructing the model to “think” step-by-step), self-reflection (re-evaluating wrong responses to lead to better conclusions), and multi-shot prompting (providing multiple examples in the prompt). These techniques eventually led to OpenAI’s GPT-4 outperforming other models by a large margin on reasoning tasks using reinforcement learning on reasoning steps (think MCTS). Yet, recent research from Apple showed that even for these “reasoning” models, the model seems to simply retrieve learned concepts during training rather than employing novel, human-like reasoning.

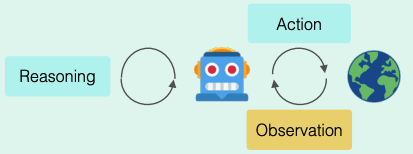

This raises the question of how to enforce reasoning in agentic systems in which LLMs might be invoked tens to hundreds of times. The best answer to date is ReAct, where the model, after each action it takes, reflects on the new information received from the environment to adapt its reasoning trajectory accordingly. This can be implemented as simply as an intermediary step in which the LLM is prompted to reflect on the current plan to solve the task at hand given all previous and new information.

Schematic overview of ReAct [5]

Tool calling

Naturally, not everything in the real world is natural language. Humans, for instance, use a lot of tools (e.g., calculators, the internet, databases) daily to fulfill tasks more efficiently—so why wouldn’t agents? This capability allows agents to take actions in the outside world (e.g., web browsing and performing API calls).

The research labs building foundational models recognized this early and started training their models to use tools. Today, most models accept schemas of tools as input (string representations of Python functions) and can execute these tools (including parameterization) during generation via special tokens introduced into the model vocabulary. Think of a tool as any kind of Python function, from those performing simple arithmetic operations to tools calling external APIs. Naturally, this brings with it the possibility for the model to take actions in the outside world. Every tool made accessible to an LLM-powered agent should be designed carefully under security considerations to prevent damage. Any unrestricted access to computer systems should occur in sandbox environments.

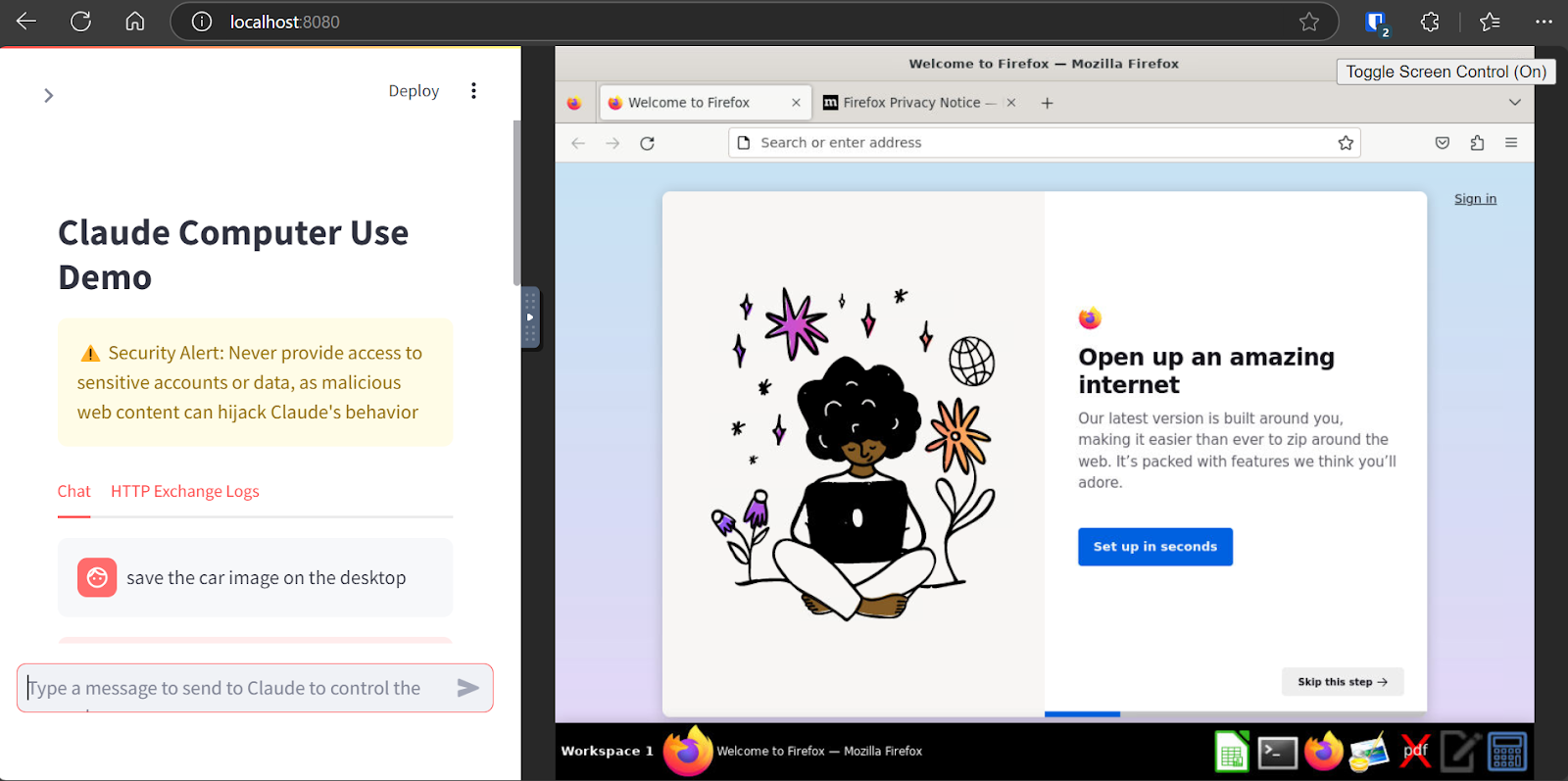

A recent example of tool calling is Claude’s Computer Use, a set of tools allowing Claude to take over your computer and use the browser like a human to fulfill queries. This works through a set of tokens that call tools such as move mouse to coord(X, Y) and left mouse click.

Anthropic demoing Claude's computer use [6]

Structured output

Structured outputs might not seem like an important feature for agents at first, but during my recent experiments with building agentic systems, I found them essential. Structured output, as provided by OpenAI’s GPT-4 models via the API, allows developers to instruct models on how to structure their output. Many applications require responses not only to be correct but also to adhere to predefined formats such as JSON, XML, or SQL queries. For example, when interacting with databases or APIs, generating valid and precise structured output is critical. Even if the model output is not directly used for an API or database, I found it essential to continuously structure the model’s output to monitor and guardrail the agent system to prevent malicious outputs.

Multi-agent

Industrialization has taught us that cross-functional collaboration fosters productivity in almost all tasks. Considering LLMs’ ability to communicate through natural language and learn from mistakes or incorporate feedback (self-reflection), it only makes sense to explore the same paradigm in LLM agents. This has led to the deployment of multi-agent systems, where multiple agents collaborate to complete complex tasks.

In multi-agent systems, similar to how teams work in companies, agents can specialize in distinct functions—for example, one focusing on reasoning, another on memory retrieval, and yet another on tool usage. By sharing information and delegating tasks, multi-agent systems can achieve higher efficiency and performance than a single agent alone. This allows tasks to be broken down into smaller, more manageable pieces, making them easier to solve for individual agents and enabling early detection of erroneous outputs via ‘Evaluator’ agents.

Looking ahead, multi-agent systems are likely to become the dominant design choice for agents, particularly given the potential to allow agents fine-tuned or preference-aligned for different chores/domains to collaborate effectively.

Examples of multi-agent systems [7]

(Multi-)Modality and Embodied Agents

One of the main limitations of LLM agents was their capability to handle only natural language. With recent advancements in multi-modal AI, agents can now process and interact across multiple modalities—such as text, images, and speech. Multimodal LLMs can understand and generate responses across diverse input types, enabling applications like medical imaging analysis combined with textual patient histories or generating code snippets based on a hand-drawn wireframe.

However, the biggest gap to bridge is the one between the digital and physical worlds. That is why most people expect embodied AI and embodied agents to become the next big thing in AI, enabling agents to physically interact with their environments. Prime examples of advances in this domain include Tesla’s Optimus robot, which uses LLM-driven intelligence to perform actions like serving beer, and Figure’s humanoid robot, which can follow instructions like cleaning dishes. These agents rely on advanced sensor integration and the real-time decision-making capabilities of the AI model powering the “agents,” enabling them to adapt and respond dynamically within physical spaces.

Embodied AI agent [8]

Orchestration

So far, we have explored the power of LLM agents and their main features. But the question of how to actually build LLM agents remains. As mentioned before, LLM agents represent a new frontier in ML engineering, which is why there are no widely adopted best practices yet. Nevertheless, several frameworks are available to help developers orchestrate LLM agent systems. Notable examples include LangChain, LlamaIndex, Haystack, AutoGen, and OpenAI’s Swarm.

AutoGen

Here, I would like to give a quick overview of the aforementioned AutoGen framework released by Microsoft researchers, which I found personally most intuitive to use.

The focus of this open-source framework is on conversable multi-agent systems. Each system is composed of customizable and conversable agents that can leverage LLM model APIs (for now, mainly OpenAI systems) for generation and tools for tool calling. These agents can receive, handle, and respond to all kinds of messages, enabling developers to program multi-agent conversations to break down complex workflows.

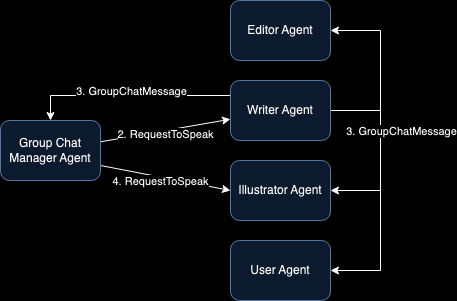

For instance, a Group Chat design pattern enables multiple specialized agents to collaborate on a shared task by publishing and subscribing to a common message thread. Each agent is assigned a specific role and contributes sequentially under the guidance of a Group Chat Manager, which selects the next agent to “speak” based on predefined rules like round-robin or AI-based selection.

For example, if we want to create a blog article including pictures, the workflow might involve defining agents like a writer, editor, illustrator, and user. The Group Chat Manager would then task the writer to draft content, the illustrator to generate appropriate images (using tools like DALL-E), and the editor to review the work. The process concludes when the user approves the final output.

System architecture of blog-writing agent [9]

Beyond this basic architecture, AutoGen includes additional features such as asynchronous execution, sandbox environments for code execution, handoff logic for Swarm-like conversation patterns, and more.

Outlook

The future of agents looks incredibly promising. I believe agents are poised to automate many repetitive and simple tasks that humans currently perform in the near future. However, significant work remains to create reliable and secure applications with agents, much like traditional software development.

A critical challenge is leveraging the “intelligence” of these systems while implementing guardrails to prevent malicious outputs. I believe hybrid systems that alternate between structured data for oversight and the latent space of LLMs for natural language understanding may be the key.

Evaluation also remains a major obstacle. Current benchmarks risk leaking into training data, while model-based evaluations often reinforce biases. Without robust and reliable evaluation metrics, deploying LLM agents in high-stakes applications will be impossible.

I believe the next big thing in AI will be embodied agents. The path to autonomous humanoid robots, capable of performing physical tasks in the real world, is clear and only a question of time (i.e., how long it will take to gather enough simulation and supervised data to train a model capable of orchestrating all sensors reliably). When these agents integrate seamlessly into daily life, the transformative power of AI will become evident to the average citizen, leading to another big wave of adoption and investment.

References

- https://regressionist.github.io/2019-05-13-Reinforcement-Learning/

- https://jalopnik.com/teslas-beer-serving-optimus-robot-was-controlled-by-a-h-1851670923

- https://developer.nvidia.com/blog/introduction-to-llm-agents/

- https://snorkel.ai/blog/which-is-better-retrieval-augmentation-rag-or-fine-tuning-both/

- https://rdi.berkeley.edu/llm-agents-mooc/slides/llm-reasoning.pdf

- https://www.datacamp.com/blog/what-is-anthropic-computer-use

- https://arxiv.org/abs/2308.08155

- https://www.coolest-gadgets.com/ai-in-robotics-statistics/

- https://microsoft.github.io/autogen/dev/user-guide/core-user-guide/design-patterns/group-chat.html